LIFE AND ACTING: Techniques for the Actor

If I were ever to stop learning about acting, I would stop teaching. So much has taken place in my education; the changes in fate during my early training as an actor led me to discover in myself an innate ability to recognize true spontaneity and an actor’s work. I searched over the years for the practical means to instigate that intuitive process and actors as well as in myself.

As I made a determined effort to grasp why at times I evoked effective performances while failing at other times, it took close to a half century of teaching acting and directing before I had the courage to write this book. To this day, through teaching I uncover fresh insights into the attainment of a truthful living performance.

The great puzzle of how to bring to life on stage, through one’s being, a character set down on paper, began for me at the age of seventeen, when I won a scholarship to enter Erwin Piscator's Dramatic Workshop in New York – famed for such graduates as Marlon Brando, Mel Brooks, Bea Arthur and Elaine Stritch – and continued when I studied directing with Lee Strasberg at the American Theatre Wing.

The performances of these actors work for me, the ultimate achievement of acting and contemporary plays. I scanned the reviews, seizing on whatever interviews the actors gave to try to apprehend the means they used to accomplish their astonishing creations. There wasn’t a word on the subject.

I have always been fascinated by – and excited to study – the preparatory sketches of prominent painters, to survey the scribbling corrections of outstanding authors on their manuscripts and proofs, and to compare them to the final works. It makes me feel present at the moment of their creativity.

At the Actors Studio, I derived the same elation every Tuesday and Friday from 11:00 AM to 1:00 PM, as they observed a stream of unknown actors – Paul Newman, James Dean, Joanne Woodward, Eva Marie Saint, Rod Steiger, Maureen Stapleton, Kim Stanley – reach for something deep in themselves to come up to the demands of scenes they chose to present on those mornings.

Their selections range from the ancient Greeks, Shakespeare, Moliere, Ibsen, Strindberg, Chekhov, and Schnitzler to an array of contemporary writers taken from novels. The failures were as engrossing and illuminating as the successes. Still, it was difficult to know how they achieved what they did.

Although unable to define the processes that great actors of the past used to achieve brilliance in their work, Lee Strasberg, nevertheless was a master at depicting how actors could, through a gesture or an intonation illuminate the works of eminent playwrights or add dimension to characters and lesser plays by ordinary writers. That knowledge instilled in us an awareness of the astonishing potential that acting could have on a play. It also gave us a necessary arrogance about the actor’s work.

The actors in the Studio, in those days, did not want to be cast in a play or a film for its own sake. Nor did they want to be used to exclusively for their personal charm or looks. They wished to be engaged for an inner sensibility, their ability to humanize to bring a living experience to their roles. Karl Malden best expressed the prevailing spirit: “I am not a job actor,” he said.

My experiences at the Studio, which I relay in this book, made me more sensitive to the truthfulness of the actor’s work. I could create conditions for creativity and actress through various means to stimulate their imagination and to bring about an effortlessness in their playing. But why these procedures worked remained a steadfast mystery to me and to the actors – and, I realized, to Strasberg as well.

Neither did we understand the components that made it possible for the actors to repeat with spontaneity what they had found through improvisation or through the situations in the play itself. Furthermore, I did not comprehend what made me choose the right actors for their roles. It would take me many years to learn the elements contained in the methods I used.

Seeing the performances of talented actors I first introduced on the stage or in film was equivalent to the excitement of unearthing some treasure in nature or to having a private moment of profound enlightenment. I found that course whenever the opportunity presented itself. Casting a pre-Broadway tryout, I called The Neighborhood Playhouse to send over their graduating class of young men for one of the leads in the play.

Out of the group I chose Steve McQueen for his first major professional engagement. When I had to replace one of the principal actors in the film version of a play I was working on, I selected George Peppard, then a student in Strasberg's private classes. George later made a stage debut in one of my Broadway productions.

I learned from the best in filmmaking as well. I stayed next to the director George Stevens on a daily basis throughout most of the shooting on “Giant.” I did the same with Elia Kazan on “Baby Doll.” The distinction in the equipment and skills required of a film director as opposed to a stage director began to clarify itself.

Carroll Baker in “Something Wild” directed by Jack Garfein, 1961, United Artists

On stage, I basically guide the actor towards a performance that finally must be totally under the actor’s command. In film, I am more like a painter, with the amalgamation of performance, image, sound, music, and editing in my hands to juggle as I see fit for the final outcome.

As a film director, I realized it was imperative to know the possibilities of all those elements. Particularly important, I discovered, is the knowledge of how to elicit a specific emotion and behavior from non-actors. Under precise direction non-actors with the right inherent personal qualities for a role are capable of remarkable performances.

When I taught film directing at the University of South California, my work consisted mainly of getting directors to apprehend, by acting themselves, how to stimulate and set the conditions for the actors for the directors to personally discover the intentions of their roles. The directors would also learn to tap into their own experience to excavate the conduct of the characters and would be poised to relay that to the actor when needed.

The greatest bounty by far that I’ve read from my profession is having had the opportunity to work directly with some of the geniuses of my time. Playwrights (whose gifts I’ve been in awe of since my school days) and their outstanding interpreters, the actors, made me perceive through our joint endeavors a sensitivity to life that constantly evolves. The acting of those works at times revealed to me a hidden, living truth that I was conscious of neither in the inert plays nor in myself.

During the last rehearsals of Eugene Ionesco’s, “The Lesson,” which I directed Off-Broadway, the author filled me with stories of his parents as the basis of the material in the play. It made me see an underlying sensuality in the cruelty, a savage humor, a form of fascistic, comic brutality in the action that I didn't fully realize until I worked on it again two decades later in my class in Paris.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Mimicking reality will not bring about creativity in an actor's work. Imitation will never reveal the real. It is only involuntary memory, the magician in ourselves, the work of the latent subconscious, that is able to grasp the experience of another.

The conscious road toward stimulating that arduous, unruly part of ourselves is a harsh, painful process for actors. It requires immersion, a descent into oneself to recognize and bring the actor close, through the senses, to another’s experience feelings and behavior.

Proust expresses it well: “Man is the creature…who knows others only through himself, and if he asserts the contrary he lies.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If little has been delineated over the centuries on the precise effect acting has had on a play, there is even less written on how the actor proceeds to appropriate a role and the way he or she fulfills its emotional and behavioral demands. Up to the 1930’s there was no mention of how actors were to condition themselves for those tasks.

For playing the piano or violin, dancing, painting and sculpting, there are entire libraries on various techniques and the training necessary to become proficient in any of them. Up to eighty years ago, Leopold Mozart had written a standard book on violin playing. A young musician could go through the steps of how to play the instrument that Wolfgang Mozart had learned from his father.

By contrast, when Stanislavsky as a young actor was taken by the performances of Eleanora Duse and Tommaso Salvini and wanted to know where he could study their approach to a role, what he had to do to be able to play with the emotional truthfulness of those actors, he was told to join acting companies in the provinces.

Playing in those troupes, he was told, would make it possible for him to attain the outstanding artistry of the actors he held in awe. That is the equivalent of advising someone who wanted to become a great violinist to play at country-dances and music-hall shows.

Stanislavsky took the advice, and toward the end of his career, after he founded the Moscow Art Theater and had become a well-known actor, he felt that it never quite achieved greatness is an actor because he had never gotten over the bad habits he had picked up in the provincial companies as a young actor.

Of course, there are been exhortations through the ages of what acting should be like. Hamlet’s advice to the players “to suit the action to the word and the word to the action” is absolutely correct. But how do you accomplish that?

Up until the time of Stanislavsky’s published work and V.I. Pudovkin’s Film Acting and Technique, there existed only two well-known books on the subject – one by Francois Delsarte filled with illustrative clichés (“Put your hand on your heart to show love” and a philosophical one by Diderot, The Paradox of Acting. In his book, Diderot is trying to comprehend the nature of an actor’s emotions on stage and the ones he experiences in actuality. He is unable to differentiate.

Neither did the great actors of the distant past leave behind any significant description of what exact attributes were essential for them to achieve their creations, nor which pitfalls they had to guard themselves against. The greatest of them were not proficient enough to cope with impediments to their performances.

Carroll Baker in “Something Wild” directed by Jack Garfein, 1961, United Artists

Eleanora Duse cancelled a performance before the Czar because she was not inspired. Edmund Kean gave the same reason for not appearing in Boston, causing riots in the city by frustrated ticket holders.

From its earliest history it seems knowing how to act was mainly an intuitive knowledge that somehow defied depiction; practitioners acquired it through years of playing in front of the public, as it was true in my own case. For some, it took years of playing to acquire methods they could put faith in.

Harold Clurman told a story about an actor during the 1920’s in a Eugene O'Neill play who, to relate a horrendous sight he had just witnessed, foamed at the mouth, screwed up his eyes, and screeched so that the words in his speech were hardly comprehensible. O'Neill tried various means to make the actor believable. He suggested subtler movements, a modulation of the voice. The ranting, even at a lower pitch, remain just that. Clurman, who was a stage manager on the production suggested that perhaps his teacher, Richard Boleslavsky, might be of some help. O'Neill, stymied by the actor, readily agreed.

After looking at the scene Boleslavsky began work in front of the entire company. He advised the actor not to gain belief through the horrors depicted in the text or in the tragedy of the plot. Instead he advised him to talk simply to other characters to make them see his helplessness in the face of a sudden force that wreaked havoc with all that stood in its way. The actor now behaved humanly on the stage, shaken and in awe of what he had come face to face with.

As Boleslavsky was leaving the theater, Otto Kruger, a star of the play who had a long history of playing, came up to him and asked him where he learned that he had just done with that actor. Boleslavsky replied that he studied at the Moscow Art Theater and at the Reinhardt Theater in Berlin.

“And how long did that take,” Krueger asked. “Two years in Moscow and nearly as many in Berlin.” “Hot damn,” the astonished actor exclaimed, “it took me twenty years of acting to learn that!”

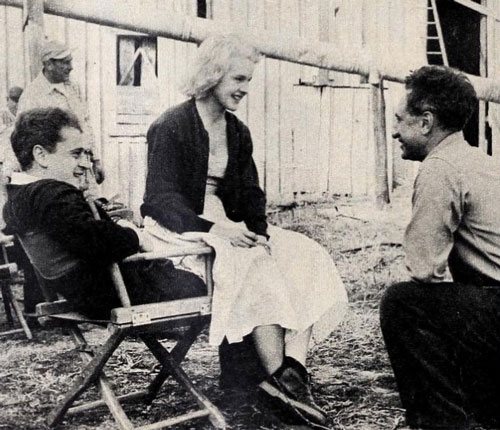

(L. to R.) Jack Garfein, Carroll Baker and Elia Kazan

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

That audiences are in wonder at an actor’s emotional transformation as well as the deeply felt impact a play or film can have on the audience are common knowledge. The human need to view actors in imaginary situations remain as veiled for me as the precise material that actors use within themselves for their work.

No one I worked with up to this time had ever given me a satisfactory answer to what I believe the two essential preambles: to grasp the processes of the art of acting art and technique. 2010

(Excerpts from LIFE AND ACTING: Techniques for the Actor by Jack Garfein. Published by Northwestern University Press, reprinted with the permission of the author, Jack Garfein.)

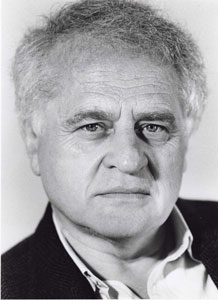

JACK GARFEIN (1930-2019) made his Broadway debut as a director with “End as a Man” with Ben Gazzara. He also gave James Dean his first role in the first Actors Studio production of the play. During his theater career on Broadway and Off-Broadway and around the world, he produced and directed over fifty plays. Some of the most notable productions include: “Shadow of a Gunman” by Sean O’Casey, two plays by Arthur Miller: “The Price” and “The American Clock,” “Childhood by Nathalie Sarraute” starring Glenn Close, Harvey Gabor’s “Rommel's Garden,” “For No Good Reason by Nathalie Sarraute, Kurt Weill Cabaret with Alvin Epstein and Marta Schlamme, Samuel Beckett’s “Endgame,” “The Chekov Sketchbook” with Joseph Buloff and John Herd,” “California Reich” and “The Lesson” by Eugène Ionesco, and “The Beckett Plays” (“Ohio Impromptu,” “Catastrophe,” “What Were”) in London, Vienna, and Jerusalem, Kafka’s “An Address To An Academy” in Paris. He directed the French premiere of “Master Harold and the Boys” in Paris, the world premiere of Beckett’s “Nacht Und Raume” in Austria. Mr. Garfein’s documentary “The Journey Back” chronicles his return to Auschwitz; he survived eleven concentration camps, including Auschwitz. At the end of the war, Mr. Garfein was liberated from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp by the British Army. When he came to America, as an actor, Mr. Garfein won a scholarship to the Dramatic Workshop at The New School in New York City. He took acting classes with the influential German director, Erwin Piscator. Among his classmates were Walter Matthau, Tony Curtis, and Rod Steiger. In 1949, encouraged by Piscator, Garfein joined The American Theater Wing to study directing with Lee Strasberg. In 1955, Mr. Garfein was officially invited to become a member of The Actors Studio. He was the first director to receive this honor. As a director and an acting teacher, he directed Uta Hagen, Herbert Berghof, Shelley Winters, Jessica Tandy, Hume Cronyn, Ralph Meeker, Mark Richman, Mildred Dunnock, Elaine Stritch, Malick Bowens. He discovered Ben Gazzara, James Dean, Steve McQueen, George Peppard, Bruce Dern, Doris Roberts, Jean Stapleton, Pat Hingle, Albert Salmi, Paul Richards, and Susan Strasberg. Garfein’s two films include “The Strange One” and “Something Wild.” In 1966, Mr. Garfein, in collaboration with Paul Newman, founded the second branch of the Actors Studio in Los Angeles. He was also one of the co-founders of New York Theatre Row, where, in 1974, he created The Harold Clurman Theater, and later The Samuel Beckett Theatre on Theatre Row 42nd Street in New York City. Mr. Garfein created a unique acting technique, which he described in his book, Life and Acting: Techniques for the Actor in 2010. He taught the craft and art of acting for over forty years in Paris, New York, London, Berlin, Madrid, and Vienna. Among his students included Sissy Spacek, Samuel Le Bihan, Irène Jacob, Sam Karmann, Bill Smitrovich, James Thiérrée, Valérie Stroh, Jacky Narcissian, Laetitia Casta, Mark Richman, Bruce Dern. In 1985, Mr. Garfein founded his own studio, Le Studio Jack Garfein, in Paris. For his teaching work, he was awarded three Masque D’Or awards in France: for best scene work, and as the best acting teacher in France. garfeinstudio.com/

by Jack Garfein

by Jack Garfein