Art is the Means by which We Make Ourselves Visible

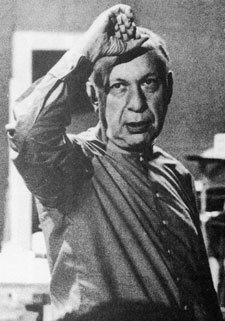

Harold Clurman by Al Hirschfeld Reproduced by special arrangement with Hirschfeld's exclusive representative, The Margo Feiden Galleries, NY

Harold Clurman by Al Hirschfeld Reproduced by special arrangement with Hirschfeld's exclusive representative, The Margo Feiden Galleries, NY

Scratch an American today and you will find worry! At first it seems only concern about economic security – the fear of hard times, the disgrace of a lower standard of living.

Deep down it is a worry about Everything! Personal relations are questioned because they have become unsatisfactory, the meaning and value of life seem uncertain as almost never before. The illusion of security we may have because of a relative prosperity only intensifies the nervousness underneath. It is as if we were thrown back to the beginning – asking ourselves all over again (or for the first time), “Is life worth living?”

In our hearts we know the question to be unnatural. Man in a state of health is inevitably struck by the magic mystery of life; this mystery, however, does not diminish his appetite for living, but rather heightens his sense of life’s grandeur and passion. When life itself is questioned, it means that some poison has begun to devitalize us, that the organism of society has become corrupt and that we are suffering from its contamination.

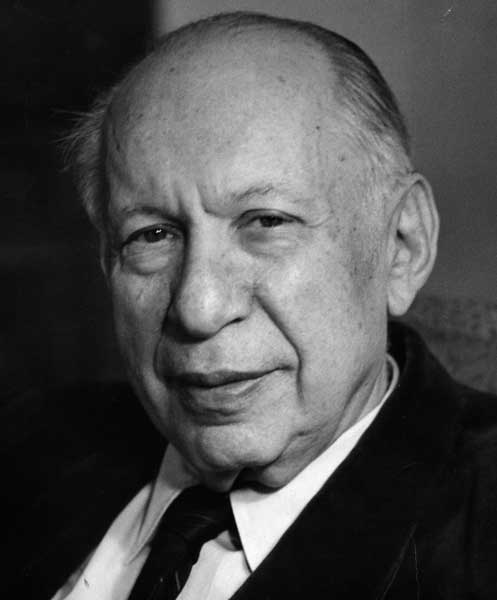

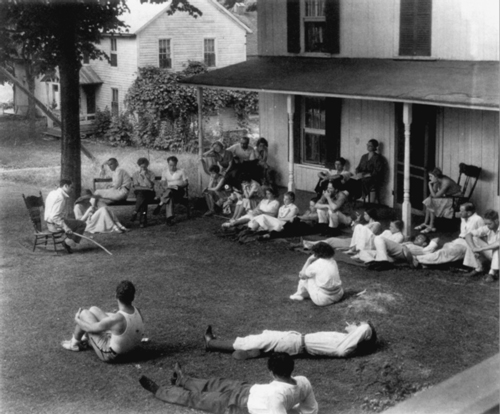

(L.-R.) Lee Strasberg, Harold Clurman and

Cheryl Crawford at Brookfield Center, Ct.

summer, 1931 (

photo: Ralph Steiner)

It is part of man’s health to seek for a cure, to go to every possible source of inspiration and knowledge for help. Thus, man, knowing that he expresses his essence in art, that art is the evidence of his deepest aspiration, the emblem of his total experience, goes to the artist for a salvaging truth beyond the clamor of editorials or political oratory.

The artists share in the universal instinct which gives us the conviction that what the artist does (creating in play forms of experience through which we both identify ourselves and communicate with others) is perhaps the noblest of man’s activities, the one most symbolic of life’s aim and meaning.

Yet the artist cannot help but realize that his freedom to exercise his faculty is being threatened, that his position in the world is not only becoming threatenedly jeopardized, but that he and his work are being rendered unnecessary, almost undesirable. The artist, losing his foothold, begins to wonder whether he is not after all an excrescence, a futile playboy, a pariah, a bum!

My own belief – which I feel it proper to reassert every time I begin anew to “cover” the season in the arts – is that if art has no meaning or value, then man himself has none.

Art is the means by which man makes himself visible.

Through art man moves towards self-realization; art is therefore a basic product of man’s living, the synthesis towards which he inevitably yearns. Contrary to the wholesome theory that art is a sign of man’s weakness.

I believe it to be the true testimony of his manhood. All men, whether they know it or not, strive to the condition which makes the artist. Everything that tends to destroy

art of the artist in man must be fought. Because nothing human can be alien to art, the artist cannot consider himself outside of anything that is of this world.

A distinguished poet has recently said that the artist’s values are “not of this world.” We all understand what the poet meant, but I think it is a misleading statement, nonetheless. Whatever values are injurious to the artist are humanly destructive, and should be themselves put out of the world. I am neither a partisan of “art as a weapon” nor of “art for art’s sake” (thought I find the latter formulation more sympathetic since I conceive of art as inseparable from a universal human concern).

A distinguished poet has recently said that the artist’s values are “not of this world.” We all understand what the poet meant, but I think it is a misleading statement, nonetheless. Whatever values are injurious to the artist are humanly destructive, and should be themselves put out of the world. I am neither a partisan of “art as a weapon” nor of “art for art’s sake” (thought I find the latter formulation more sympathetic since I conceive of art as inseparable from a universal human concern).

“Pure art” is pure nonsense, and my objection to “art as a weapon” does not arise from a scorn of weapons – they too may be creative instruments – but from a refusal to limit the function of art. “Art as a weapon” is a slogan that usually emanates from the same narrowly utilitarian conception of life which hold that art is justified only as publicity serve for toilet articles, household goods and insurances companies.

Art gives content to life itself. The enemies of art are the great betrayers and malefactors of humankind. It is part of the critic’s job to praise life where he finds it and denounce everything that conspires against it.◆ 1948 Excerpt from the essay: “The Threshold of a New Season.”

The Group Theatre at Brookfield Center, Connecticut, summer,

1931 (photo: Ralph Steiner)

HAROLD CLURMAN Considered the “most influential figure in the history of the American Theatre,” co-founder of American’s foremost acting company, The Group Theatre, award-winning director of over forty of the most important plays of the 20th century, Clurman’s original Broadway productions include “A Member of the Wedding” with Julie Harris, “Bus Stop” with Kim Stanley, Clifford Odets’ “Awake and Sing” and “Golden Boy,” and “The Waltz of the Toreadors” with Ralph Richardson. He was recognized as America’s foremost drama critic, and was the author of seven books include his autobiography All People are Famous, The Divine Pastime, Ibsen, Nine Plays of the Modern Theater, and two of the theater’s most influential books, The Fervent Years and On Directing. Most of his essays and reviews can be found in The Collected Works of Harold Clurman. He directed around the world including in Israel (“Judith”), Japan “Long Day’s Journey into Night” and “The Iceman Cometh” with Kumo Theatre Company, and in England “Tiger at the Gates” with Michael Redgrave. He wrote for “The Nation” among many other newspapers and magazines, receiving France’s Legion d’Honneur. The inspirator of The Group Theatre, beginning in late 1930, Clurman gave weekly lectures on the benefits of a permanent acting company. He believed that once actors knew and trusted each other they could truly work together to create great theater. In 1931, together with Lee Strasberg and Cheryl Crawford, they gathered 28 actors and formed The Group Theatre. Over the years The Group Theatre, considered America’s greatest ensemble Theater included Stella Adler, Robert Lewis, John Garfield, Morris Carnovsky, Phoebe Brand, Elia Kazan, Clifford Odets, Franchot Tone, Lee J. Cobb, Karl Malden, Paul Green, Martin Ritt, Sidney Kingsley, Mordecai Gorelik, Sidney Lumet, Frances Farmer, and Sanford Meisner. The success of the Group Theatre prompted many other companies to embrace the ideas of Stanislavsky. The most successful of the Group Theatre’s plays were those written by Clifford Odets, including “Awake and Sing,” “Golden Boy” and “Waiting for Lefty.” Though the Group Theatre lasted only ten years, it produced twenty plays and brought an excitement to the American stage that still remains. In recognition of his great influence and commitment to the arts, Clurman was awarded the rare honor of having a theater named after him on 42nd Street in New York City.

Harold Clurman by Al Hirschfeld Reproduced by special arrangement with Hirschfeld's exclusive representative, The Margo Feiden Galleries, NY.

“Listen to that voice inside that helps you. Be very careful, don't let the source get dried up. Only your deep need to salvage something from the void – to act, to write, to create, not to have a “profession” – can keep you from the commonplace and from dying out. But you must have a deep recognition of your solitude to live the way you should live, not the way it is agreed upon, and not to fall for this big thing around you. Being in the theater means learning about yourself. You have to dump the insignificant in enrich yourself with its truths.” - Stella Adler