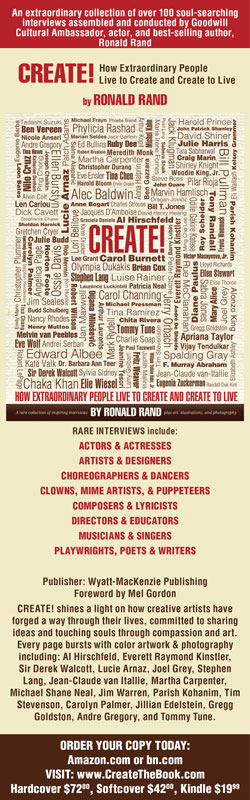

Brian Cox

The Game

An actor of extraordinary stature and depth, recently played Vladimir in “Waiting for Godot” with Bill Paterson at The Royal Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh, Scotland. Mr. Cox was a member of the Lyceum company in Edinburgh, the Birmingham Rep where he played the lead role in “Peer Gynt,” and Orlando in “As You Like it,” and soon made his London debut in 1967. His many stage roles include as a member of the Royal Shakespeare Company and London’s National Theatre during the 1980’s and 1990’s as the title character in “Titus Andronicus,” Petruchio in “The Taming of the Shrew,” as Burgundy opposite Laurence Olivier in “King Lear,” and later went on to play King Lear at the National Theatre. He also played Inspector Nelson in “Rat in the Skull” (Laurence Olivier Award as Best Actor). More recently, he appeared in Broadway in “The Championship Season,” and in “The Weir” at The Donmar Theatre and Wyndham’s Theatre. His many TV and films include “The Wednesday Play,” “The Year of the Sex Olympics,” “The Prisoner,” as Henry II in the BBC2’s “The Devil Crown,” as Leon Trotsky in “Nicholas and Alexandra,” “The Lost Language of Cranes,” “Sharpe,” “Grushko,” “Reign Storm,” as Hermann Goring in “Nuremberg” (Emmy award, Golden Globe & Screen Actors Guild noms.), “Frasier” (Emmy nom.), “L.I.E.” (Boston Society Film Critics Award, Dallas-Ft. Worth Critics Award, Independent Spirit Award, National Society of Film Critics Award, NY Film Critics Award & Satellite Award), as Jack Langrishe in HBO’s “Deadwood” (Screen Actors Guild nom.), “Zodiac” (Satellite Award nom.),“The Autopsy of Jane Doe,” “Doctor Who” Christmas Special: “The End of Time,” “The Big C,” “The Straits,” “Rob Roy,” “Braveheart,” “Adaptation” (Screen Actors Guild nom.), “The Ring,” “X2” (Teen Choice Award nom.), “Try,” “The Bourne Supremacy,” “Red,” “Chain Reaction,” “25th Hour,” “Super Troopers,” “Red Eye,” “Tell-Tale,” “The Escapist,” “The Day of the Triffids,” and “Rise of the Planet of the Apes.” He has narrated several audiobooks including Ivanhoe, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion, and The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrun. Mr. Cox received the 20th Bradford International Film Festival Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2010, he was elected as Rector of the University of Dundee. A patron of the Scottish Youth Theatre, Scotland’s National Theatre “for and by” young people in Glasgow, a patron of “THE SPACE, a training facility for actors and dancers in Dundee, and an ‘Ambassador’ for the Screen Academy Scotland. In 2012, he was the 10th Grand Marshal of the New York City Tartan Day Parade. Mr. Cox was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

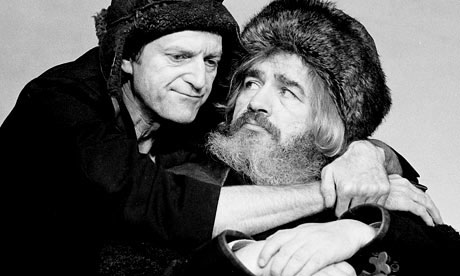

Bill Paterson and Brian Cox in Waiting for Godot

Recently you brought Vladimir to life in “Waiting for Godot” with at The Lyceum in Edinburgh which you actually joined in 1965. Why did you want to take on this Beckett play at this time in your life and were there certain challenges tackling on the role?

I suppose the appeal of something of “Waiting for Godot” is that the play deals with the most fundamental issues of the human condition. A narrative unfolding within the premise of: for ‘Who, ‘Why’ and ‘What’ are we waiting. A profound questioning of humanities purpose.

Seen through the eyes of two travelling itinerant figures seemingly locked in a wilderness landscape. Two men of a mature age, each encompassing the polarities of optimism and pessimism. Further polarized by the arrival of an archetypal Master/ Servant duo. Whose complex relationship undermine any notions of equanimity, which only exacerbates our duos already questioning state. Questioning in a sometimes bathetic sometimes hilarious and sometimes poetic manner the validity of their lives.

The play from the actors’ point of view makes extraordinary demands on the range of their individual skill and demands nightly a huge leap into the unknown. It is by far and away the most demanding play I’ve ever performed. Embracing a whole variety of performance skills.

For me at this stage in my career, there can be no more profound resonance than the embracing of such a master as Samuel Becket.

Did you have a great desire early in your life to go into the theatre?

I suppose my first experience of theatre was as a small child aged about two, when my father put me on top of the coal bunker, in the window recess of our tenement apartment, in my home town of Dundee. At that ripe old age of two, I would perform to much applause the repertoire of Al Jolson with full actions and mimicry. I think this probably was my first taste of theatrical desire.

But honestly, I really can’t remember a time when I didn’t want be involved in some form of performance. The cinema was a huge influence on me as a child, and I suppose ultimately led to my desire to become an actor. I didn’t experience the live theatre till I was about fourteen. Then my desire was confirmed. From then there was no looking back.

Who were important inspirations when you began working?

I can consider myself incredibly lucky in the range of incredible directors, actors and teachers who have inspired and mentored me throughout my career.

I sought those influences from a very early age. I think this is due to the fact that my father died when I was eight years old. So I was incredibly open to those I considered wiser and more practiced in their various crafts.

Teachers at my school: Bill Dewar and George Hackett. My formative schooling was pretty disastrous. But these two men saw something in me that went beyond the bounds of formal schooling and encouraged whatever embryonic talent I had to seed. I shall be eternally grateful to them.

My early days working at Dundee Repertory Theatre. Where I started at the age of fifteen. During my time there so much kindness and consideration was afforded me, that I could not fail to blossom.

Tom Stoppard’s Rock n Roll on Broadway

The Voice coach Kristin Linklater, who was invited to join the voice classes she was giving at the Rep convinced me to audition for the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art.

The actress Susan Williamson who tutored me in my audition for LAMDA.

My time at LAMDA working and learning with the rigorous Vivian Matalon.

The tremendous and beautifully eccentric Michael McCowan, Principal of the school. Who instilled in me a considerable sense of wonder at my chosen profession.

Then my earliest professional acting experiences. My acting debut at The Royal Lyceum Theatre under the Visionary care of Tom Fleming. It was at the Lyceum I met my lifetime mentor the Scottish actor Futon MacKay. A man of great insight and perspicacity, who always reminded me of the tremendous respect that is needed for the art and craft of acting. I was very ambitious when I was younger. (The old tramp in that wonderful movie, “Local Hero.”) Fulton was always there with a perspective that was always grounding. He used to say of my ambition, in his rooted Scottish vernacular, “Dinnae (Don’t) worry about being a star, Brian. Just say your prayers and be a good actor.” As if to say, ‘the job is hard enough without confusing it with the other crap.’ To this day it's the best advice I've ever had. Fulton was both the voice of conscience and consciousness. He has been dead for nearly thirty years and I still miss him.

Other influences in my life were the director Peter Dews, who gave me my first string of Shakespeare roles at Birmingham Repertory Theatre. An ex-teacher who had an extraordinary motivational grasp of Shakespeare's language, both in its poetic and psychological muscularity.

The great Lindsay Anderson, who instilled in me, the art of being on stage. His great acting note to me in my debut at London’s Royal Court Theatre in David Storey’s family drama, “In Celebration.” He said: “Brian, don’t just do something! Stand There!”

And last but not least, Michael Eliot, co-founder of The Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester. Father of the supremely talented, Suzanne Eliot, of “War Horse” and “The Curious Incident of the Dog at Night” fame. Michael was a Titan of the theatre a director of impeccable integrity and vision. He opened me up to the works of Ibsen. He was the son of King George VI’s chaplain. He brought to his productions of Ibsen, Shakespeare and T. S. Elliot, a zealot-like religious fervor which never failed to inspire to the highest degree.

Titus Andronicus

Among the herculean roles you’ve assayed include Titus Andronicus and Petruchio at the RSC, as well as Burgundy opposite Laurence Olivier when he played King Lear. And then you played King Lear at the National Theatre in London. How did these roles test your mettle and what did you discover about your abilities and craft and use of language as you forged headlong into them?

This is a perfect follow-up to the inspiration question, in as much as my re-awakening of my relationship to the bard was through my working partnership with Deborah Warner on “Titus Andronicus” and “King Lear.”

Brian Cox as King Lear with David Bradley as The Fool

Deborah was an incredibly liberating force. As a result, I took a lot of risks in the creation of both roles. Risks involving a much deeper and profound sense of physical freedom. Creating a greater range in performance.

To be fair, the renaissance in my acting began six years before Deborah and I worked together. I was playing in Macbeth in India. A production that had begun at The Arts theatre in Cambridge. When I reached Bombay a young woman, a Katak dancer was assigned as my dresser. She was sixteen. At every performance she would stand in the wings watching, nay scrutinizing my performance. After the second matinee she approached me.

“Mr. Cox,” she said, “May I say something about your acting?”

Me, taken aback, somewhat nervously “Of course.”

“When I watch you on stage, I feel you want to go further than you allow yourself. I feel you want to dance when you act. Your voice wants your body to move. To make the same movements in the air your wonderful voice makes.”

I was shocked by what this sixteen-year-old said. I was shocked because she was searingly accurate in her observation. For years I had felt there was this barrier to achieving what I wanted to achieve as an actor. But I didn’t know what that barrier was. And here, in a single paragraph, this young dancer had not only acknowledged ‘that barrier,’ but her very utterance had precipitated its demolition.

From then on at every performance I had her observe and note me. To the point where in Macbeth’s ‘dagger’ speech, I was virtually crawling all over the stage. And at every performance she would tell me to go further.

Acting is a skill that you never ever stop learning and refining.

By the time I came to play Titus Andronicus, I was ripe to move into a whole new territory. Titus was, of course, the perfect vehicle. This was a play that had defeated many actors over the years. Peter Brook had done a memorable production with Laurence Olivier in the mid 1950’s. It was a production of inordinate depth. But apparently the absurdist elements had been a little excised.

The Titus of myself and Deborah was very much the product of a post-Becketian age. An age that was ripe for embracing the elements of Titus that were both absurd and ludicrous. Drama of the past embraced the dualities of comedy and tragedy. But towards the end of the twentieth century, and in the wake of the holocaust and the insanity of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And even to the current craziness of the Middle East, a new mask has entered the arena of the theatre. The mask of the ludicrous.

And never there was never a piece of drama that embraced the ludicrous more than “Titus Andronicus.”

In “Titus” it is Shakespeare’s embracing of the extremes of Titus’s suffering that gives the play its extraordinary dimension. Also as a burgeoning playwright it allows him to first lay-out and experiment with ideas and themes that are the foundation of many of his later plays. “Lear,” “Hamlet,” “Othello,” “Coriolanus.” Themes such as: grief, aging, madness, jealousy, self-obsession, treachery, self-righteousness. A whole gamut of ideas and themes that contribute to his ultimate greatness as a playwright.

“Titus” truly is the template of the great master-works to come. And. of course, for the actor. It’s a tremendous gift. Consequently, when I came to play Lear, Titus had already prepared me for the tragic path of the doomed and disillusioned King.

You’ve also created many memorable performances in such films as: “Rob Roy,” “Braveheart,” “The Ring,” “X2,” “Troy” and “Chain Reaction.” What led you to want to perform in film?

In the late 1990’s, after performing in and out of the Theatre for thirty years plus, I decided it was time to professionally revisit my first love...Cinema. After all my introduction to the Dramatic Arts as a young lad was through Cinema.

In my home town of Dundee in Scotland when I was a boy, there was as many as twenty-one cinemas and between the ages of six and eleven I had visited everyone. It wasn’t British cinema, which was essentially feudal in concept, forelock-tugging and patronizing but American cinema, which was wholly egalitarian. Anybody doing anything at any time. The range of American Cinema was astonishing – the zany comedies from the Marx Brothers to Preston Sturges; the westerns of John Ford through Anthony Mann and John Sturges. The ‘noire’ of Howard Hawks through John Huston. The modernists of the 1950’s – Elia Kazan through Sydney Pollack. The advent of CinemaScope, Vista-Vision, and Cinerama.

To be a child at such a time was a joy. And the Cinema was the temple of that joy. So in the mid ‘90’s my pursuit of a cinematic career was long overdue; I had dabbled from time to time. I made my first film in 1971. “Nicholas & Alexandra,” in which I played Trotsky. I had made a movie directed by the great Lindsay Anderson in the mid ‘70’s – “In Celebration.”

Then I worked between theatre and television until 1985, when I made a dual appearance in New York City, first in O'Neill’s’ “Strange Interlude” on Broadway, then at the Public Theatre in “Rat in the Skull,” which transferred from The Royal Court Theatre in London.

From this I was cast as Hannibal Lector in the movie, “Manhunter,” which quickly became a bit of a cult classic. This in turn led to many doors being opened for me in Hollywood. But as I say, it wasn’t till I had honored my classical career at the RSC and the RNT. I decided it was time to switch my attention to my childhood dream of Movies. I was almost fifty when I made that decision.

I had seen Jason Robards play the role of the coach in “That Championship Season” and was fortunate to see your performance on Broadway in a revival of the play. What is about that role and play that drew you to want to take it on?

The Championship Season

For me, “That Championship Season” is one of the great American plays of the twentieth century. Because it tackles through a sporting metaphor the great archetype of ‘The American Dream.’ The great fear that is surprising – central to American life – which is not living up to expectations and the misery that creates in the American psyche. The pressure of too much early promise and the deception that all too often goes with that promise.

The play surgically examines in great detail these issues in a tremendously humanist fashion. The character of ‘The Coach,’ which I played, is in himself the false prophet of a better life to come. A great role in a great play.

You also acted in the TV series “Deadwood” with your wife, Nicole Ansari, a very gifted actress. I had the privilege of seeing you both in Tom Stoppard’s “Roll ‘n Roll” on Broadway, and I was fortunate to work opposite her this past summer in “Hamlet.” What has it meant for your life and work having Ms. Ansari as your partner and wife?

Deadwood

I regard myself incredibly lucky to have Nicole as my partner. Not just because she is a very loving, honest, caring and empowering person. But also because she is a phenomenal artist. Both as an actor, and as a great discerner of talent – we’re so much on the same page. In my life I have never been involved with someone so astute about their craft.

I regard myself incredibly lucky to have Nicole as my partner. Not just because she is a very loving, honest, caring and empowering person. But also because she is a phenomenal artist. Both as an actor, and as a great discerner of talent – we’re so much on the same page. In my life I have never been involved with someone so astute about their craft.

Why do you love Shakespeare as much as you do?

You simply can’t get round Shakespeare. His writing covers the entire human experience. I was once in a production of a Shakespeare play. I won’t say which one but I was very unhappy in it; I was committed to quite a long run of this play.

After my initial misery I decided that I would work through my unhappiness by a detailed study of the play. I compared it to doing a marathon run and that moment when you hit the wall and break through to a new energy. My understanding of the flaws in the production of course created bias. So I had to rise beyond bias to a more open understanding of the plays dramatic potential. This production had created in me an intense dislike for the play.

So as I was performing, I kept re-envisioning the play in a myriad of settings and scenarios. Coming to the conclusion that the play’s power superseded any inadequate production. As Hamlet so rightly says: “The play’s the thing....”

The circle was completed, when four years later, I directed this very same play to much success and satisfaction. The level of satisfaction in a fine production by this extraordinary playwright can be, at times, beyond words.•