An Account of a Conversation with Jerzy Grotowski about Theatre and Paratheatre - November 8 and 9, 1977

(This is the first time these talks have ever been published for the public.)

FIRST SESSION – November 8

On two evenings, November 8 and 9 of 1977, Jerzy Grotowski held a conference in Portland, Oregon on the Lewis and Clark campus. During those two evenings, a Tuesday and Wednesday respectively, he answered questions from the audience. The first session began at eight in the evening and ended at two in the morning. The second session began at eight but at midnight Grotowski began individual interviews with people who were interested in going to Poland that year for a longer paratheatrical event there. This record is of the conference prior to the interviews.

On two evenings, November 8 and 9 of 1977, Jerzy Grotowski held a conference in Portland, Oregon on the Lewis and Clark campus. During those two evenings, a Tuesday and Wednesday respectively, he answered questions from the audience. The first session began at eight in the evening and ended at two in the morning. The second session began at eight but at midnight Grotowski began individual interviews with people who were interested in going to Poland that year for a longer paratheatrical event there. This record is of the conference prior to the interviews.

Grotowski spoke French, which was translated by two language professors from Lewis and Clark. Neither was accredited as a translator and only one had any theatre background. Despite these difficulties, the speaker and his audience developed a rapport that encouraged frequent applause and laughter on the part of the audience, and an animated, physical performance from the speaker. As can be seen from this record, highly personal topics were dealt with and encouraged. This record is not a literal transcription of what was said. There were no recording devices used; instead, I wrote as quickly as possible, often having to paraphrase in order to keep up with the speaker and because the translation was not always accurate.

Grotowski spoke in a theatre designed to hold some four hundred people. About two hundred and fifty people attended and at least a hundred of those remained for the personal interviews. When we initially assembled, the department chair gave an introductory speech about Grotowski’s work, which he broke into two phases: the first covered the period from 1959 to 1970 and involved all the productions of the Polish Lab theatre chronicled in Towards a Poor Theatre and in Raymonde Temkine’s Grotowski. In 1970 Grotowski began a new phase of work called paratheatre, Mountain of Fire, or simply “the work.” Under the direction of Teo Spychalski, a member of the Polish Lab Theatre, several of us in the audience had participated in paratheatrical experiences the weekend prior to this conference. An account of my experiences in these workshops is published in a separate text. They may illuminate some aspects of this part of the work.

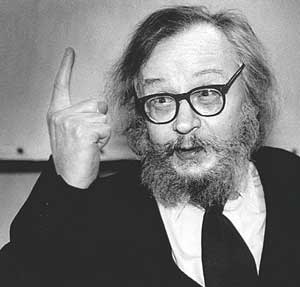

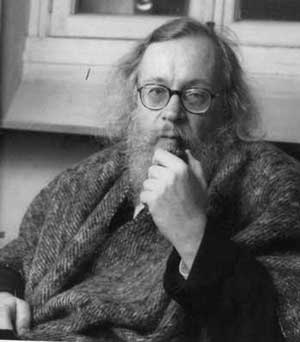

Grotowski, who was rather thin, wore a white, long-sleeved shirt, open at the neck, a brown and white sweater, black jeans, and scuffed army boots. Heavy, black-framed glasses increased the brightness of his eyes. A short beard and mustache and shaggy hair over the ears and collar gave him the same basic look as artists and students everywhere in the late 1970’s. He seemed to change drastically in physical appearance from subject to subject, from answer to answer, from person to person – now tall and stalking, then small, pixie-like almost dancing, then professorially puffing a pipe, deep in thought, then twisted into a painful grimace and posture, as if trying to wrench the immediate moment into the eternal to make his point. Frequently, he looked like a mischievous elf.

What follows is necessarily subjective. That our predilections were sympathetic must be understood to fully comprehend what is written here. It is hoped, however that the reader will see enough of Grotowski through this shaded vision to make the reading worth the effort.

He tended to take several questions from the audience at once before launching into his responses.

Question 1: Is Grotowski leaving theatre behind, or is he redefining theatre?

Question 2: Have you moved on because you had difficulty finding the necessary myths in theatre?

Question 3: How is the new work progressing and what is its future?

Question 4: Do myths not occur in everyday, mundane life, and therefore in everyday theatre?

Question 5: How much has your work been influenced by Meyerhold?

Question 6: What makes your new work different from modern religious cults (EST, Life Spring, etc.)?

Question 7: Is what you’re searching for a commonality beyond ritual or myth? Are you trying to transcend them?

Question 8: What from your first phase of work do you still feel is good? What do you now reject?

FIRST SESSION – November 8

GROTOWSKI: Problems arose through the formulation of our work. For example, is this an enlargement of theatre, or a post-theatre, or another notion of theatre, or is it the word ‘theatre’ being digested? I was never interested in making theatre for theatre, for the word, not for the sake of being a ‘man of the theatre’ – I don’t think that being a man of the theatre is very honorable. I see no purpose in striving to be that.

Theatre is only the terrain for certain work, even more than work – certain human experiences. Also it was a terrain to realize and create myself in the eyes of others. This is childish but it must be accomplished first. It is better to become someone, to understand that this has no importance at all, than to complain for a lifetime that it never happened. I wanted to realize myself in the social sense, not through money or social status, but through a creative art – creatively, to do the possible.

So I searched for a terrain where I could be totally autonomous. In theatre you can choose people for the members of the group. Theatre is a terrain where a group can be together. I don’t talk about theatre specifically, or audience, but group.

I have never loved the theatre as a cult. It’s a mystery to me, those who love the cult of the theatre. What theatre? “I love all theatres, every theatre.” This reminds me of horses trained for the circus. They march to the sound of the trumpet. With the cult of the theatre it’s the same. There are people who love the backstage. “J’aime la coulisse.” There are people who have never experienced these emotions. For me, theatre was a place where I could explore relationships.

Speaking of theatre as having a value in itself makes no sense to me. I could agree that what we are doing is similar to theatre. I could also agree that it is not theatre at all. This is just word-play.

At a certain moment in 1970 I noticed two things. To the professional world I began to function as a symbol of professionalism, which hampered me. When I say professionalism, this is not the function of being a professional actor, as I myself was a professional stage director. There is one question: is this creative? Professionalism is a certain idea of the thing. What idea? The tricks or the gimmicks you can learn? If you know how to use these gimmicks, to manipulate them, you can create something and earn money, your living. What one does is not important – which director or group you work with. What is important is social status, not human importance. This is very close to prostitution. It is this side of professionalism that is suspicious. You know certain tricks and perform them for money – like a prostitute. In 1970 I began to see that people viewed me as a symbol of this.

Secondly, I noticed a difficulty in communicating, making clear to others what they do not know. Everyone wants to understand what he already knows – no-one wants to know what he does not know. This is disappointing.

In 1970 it was clear that we were going to engage ourselves into an unknown area: the unknown territory was our direction. But it was necessary to be understood by our colleagues. How? You have to pass a very strong sign. I passed a sign formulated as the abandonment of theatre, to make people understand that this would be something not yet in existence. I tried to communicate the unknown aspect of my direction. The mechanism of production was unknown. It would not be theatre, but people would meet. If it is not theatre, it must be a religious cult or therapy – these are the two things that people know. This appeared immediately in the 1970 questions. Now that we know this unknown thing a little, I don’t care what you call it – theatre, or a bird, or something else. The name has no importance.

What is the future? In my life, I have seen many people who have created artistically ask what will come in the future. There are thousands of programs for the future, but when one is engaged in his mind with the future, he does not do anything. Our vision of our work is not what is important. What comes from our work is most important, not what we think of it. In order to have something come from the work, it is necessary to really do the work. You must think of the present. Forget every notion of the future. Concentrate on what is there and do the things that you like to do, things that devour you, things that are an irresistible temptation for you. That is what must be done, not to worry about the future. If what you do is real, it will find a future. If you think about the future, you miss your work. This word ‘future’ is castrating – a paper tiger that menaces us.

I work on what is necessary. If you act under the influence of the future, you act under the influence of fear – fear of the loss of money, position, etc., and you die. If you do what interests you, if you are aware without illusion and do what is necessary, exactly the opposite happens. Acting under the influence of the immediate, the problems of the future instantly evaporate. This is thinking in a strategic way, but the strategy serves what you want to do. Usually it is the opposite case. Most people lose their lives doing what they don’t want to do. They work to insure their strategic vision, the strategy of the future, doing what they don’t want to do. This is crazy. Strategy comes from doing what you want to do. Everything begins with what you want to do in the present sense.

I could speak in terms of the limits of the future, but this would be a diplomatic lie. For example, when I have to go to ask for money, the foundation says, “What is the future of your work?” I have five, ten, fifteen versions of the future, in this case. They are all possible. Everyone can play this game, but I don’t take it seriously, in the matter of bringing the unknown to the present.

All of the descriptions of our work in the first and second phases referring to myth and ritual – certainly at certain periods in the past work there has been a fascination with myths and archetypes. This was a very short period. If you don’t manipulate mentally, if you let come out what conditions you, if you are sincere, certain ritual and mythic situations will appear. They will appear truly and of their own force. When you speak of rituals, myth, etc., scholars and professors found those words. For example, someone who is truly religious, that is someone who goes to mass, is with the body and blood of his Lord, who experiences transubstantiation--for that person, is it a rite? No, it is something more extensive, more personal. For the scholar/professor, it is a rite.

There are certain events in the lives of people that repeat themselves and consequently function as a kind of myth. For the Poles there is a notion of sacrifice in a deadly battle which is lost, and in which one loses one’s life. The sacrifice is for the native land, which, thanks to blood that flows from our bodies, has stayed fertile. The land is nurtured, although occupied by enemies. The nation survives, stronger than our enemies. This is an old national myth. Words are not necessary to communicate it. This acted within us when we did the Constant Prince, but not because we had formulated ideas about the myth, but because it acts.

One day, after the Constant Prince, I received a letter from an old gentleman. This old gentleman lived on my family’s old ground, my family’s lost land. My family had lost this land because they had participated in several revolts. They became, therefore, wandering people, which I think is a positive thing. This is a positive story. The man wrote that during his childhood a new church was being constructed in the area. During construction, in the bottom of the old church, they found some tombs of my ancestors. One was strange. It had the engraving of a cavalier, a knight in armor wrapped in a red cloak. On the grave was written that he had been engaged in a battle in the East in the Sixteenth Century. He fell into the hands of the enemies, and because he refused to give them information, was tortured to death. His pregnant wife, after giving birth to a son, took several knights on an expedition of over 1,000 kilometers to find the body. He had made this sacrifice that I spoke of for his native land. He was wrapped in a red robe as a symbol of the sacrifice of his blood. In the Constant Prince a red robe was used in the same sense. The old gentleman wanted to know if I had known the legend. I had not. Fortunately, my ancestors lost their residence and were forced to make their living by their own hands, not the hands of others. This is good. The story of my family was half forgotten and never told.

For professors there are two reasons why this emerged in this production: 1. this is a genetic myth, an archetype, or 2. a family myth. The second one is right - not a family myth, but a myth of our people. My ancestors and I and all our people act under the same influences. When I asked the Constant Prince to use the red robe, I had no idea why. I didn’t think, “This is a symbol.” It was something that was obvious. It existed. When my colleagues asked me why, I said just do it and don’t ask me why. If I had formulated a myth prior to the work, it would have been sterile. When I obeyed that which conducted me, there evolved what people call the myth. That this was true is proved by the old man’s letter. After the letter, I know that I had acted under the influence of the same myths of my ancestors four hundred years ago. I did not do this intellectually. I didn’t say, “Find myths in the work, then everything in our research will be interpreted in this way.”

There is a long way in the night. One comes out of the city and goes to the forest. It becomes night, and because it is dark, one does not know where to step. One lights a fire to see where one is – to show the way. On the way there are rivers to be crossed. This is preparation for an action we do together. We are used to receiving things in a well-done manner, with preparation.

You must cleanse yourself of the need to prepare everything. Cross the river without searching for the comfortable bridge – not sleeping when you want to, you find yourself in an uninhabitable place, without cigarettes, flashlight, or a coca cola bottle – no screaming. You have to find reciprocal presence – the presence connected with very simple but shared experiences. After the first few hours, one begins to discover a certain way of going, not a way of violating space, but of living with it – communion with space. One discovers that one can float a certain way; the force of gravity is surpassed. Normally gravity imprisons us, and we struggle against it. Humans are used to being conquerors. But gravity is the same as the struggle against it. We train ourselves to violate gravity, but if you’re in the proper condition (the proper position), gravity can be a fuel. It’s like floating in the air – obey, do not conquer. The body knows of itself how to penetrate space. This can be discovered while creating the proper condition – in the way in the night. You need help, of course, or you would know it already. But if you get a non-verbal suggestion, you can discover it, and simultaneously, discover present time. You no longer worry about when you arrive – you discover present space.

Man is used to conquering space. He is always in his car. He leaves the city and thinks he must arrive at a point – a symbol of the future to reach. What is on the road is annoying and must be conquered. In New York City I have seen some people who walk through the streets wearing earphones. This is understandable. We must isolate ourselves with music or in a car in order to get there – to arrive. The road is bad. Points of departure and arrival are the only things that are important. Everyone asks, “Is it far?” Everyone always asks, “When will we get there?” But at the moment when you discover gravity as a fuel, when you learn to live and experience space as a bird lives and experiences air, in this present moment, then you find present time. You must stop asking, “When will we get there?” Not completely, but this question becomes secondary to your awareness of the road. This is a source of great energy, a value in itself, like a growing tree, very strong, very strong. You experienced this when very young, but then you forgot it.

When you arrive you are carried by this energy. Something happens between people that is impossible in normal life, something that is explosive. Everyone is an extension of everyone else, as if a current of energy passed through them all, through the earth, trees, space, etc. Watching, one wants to put it into words. One calls it “rites of possession,” or “ritual.” That the elements were used in this rite, like earth, air, fire, water, this is true. Rivers were crossed, people did breathe; they even walked on the ground. And what has happened is a rite of mystery. From this external point of view, all this is evident, obvious, true. This phenomenon of contact is analogous to the ancient rites. This did not appear because we searched for the rite, but because we discovered the present.

One shouldn’t look for formulae. If we define ritual and myth, the definition controls our conception. Ritual and myth are in daily life, according to the definition. Some plays have a side that catches ritual and myth as in real life. It’s true that in daily life you find the myths, but this is dangerous to manipulate.

I think the adventure of theatre, of doing performances, was beautiful. For me, this has had a completely intimate effect. Through theatre I made a step-by-step discovery of things otherwise not learned. At the start of my career as a director, I thought what was best was to show an interesting vision of staging. So, I made architectural designs, edited the text, changed the scenery and audience, etc. I enjoyed the effect of surprising the spectator, of showing different aspects of theatre. I felt the actor should be trained – capable. He must not let himself be swept into the incapacities which ordinary men enter into when aging. He must struggle to keep the motor going. I thought, this is direction: the conception. Later, I started to realize this vision in rehearsals. But every time I found something that was alive in the work, it always went against my vision. After a while I left the living things in, if they did not interfere with the vision. Later still I left myself at the mercy of these living things. I followed my temptation. I sought living things and followed their traces. I followed my temptation. I sought creativity – always. And always in the moment when it appears, it cannot be projected and therefore realized, but it can only be seized like a butterfly. It is an immediate opportunity that must be followed. It will lead us to creativity.

I learned many things from theatre, some early, some late, but always from following traces of the immediate. When you attempt to do this, there are two threatening deviations. They are subtle. The first is that you assume that you can do anything and it is fertile. But, really, anything leads to repetition of your conditioning – one really acts out the clichés, stereotypes, and banalities of one’s own life. This leads to being swept away by banal daily life, and one loses the opportunity to catch the moment.

The second deviation is not to follow the trace of the immediate, but always to do something else, something different. There are theatre groups who rehearse by improvisation – in stages, side by side, like the stages of a missile – little compartments. This is like the flights of a chicken – up and down, up and down, flying, bouncing, not really flying. Real light goes like this: pshew. He gestures with his hand like a rocket taking off.

When I decided that the immediate was my project, I saw that living beings and not thoughts, thoughts, thoughts give it birth. It was not the ideas of my colleagues that gave birth to this creativity. It was my colleagues themselves. Their encounter and connection created the opportunity.

After this I had to face a problem. I wanted to create, but I couldn’t. I wanted to be creative, but I wasn’t when I only did my projects. We were creative only with each other. Already this has changed my creative and personal life. I had already decided to eliminate all that which was not alive in theatre – stage, props, costumes, etc. The only necessity was what happens between human beings. Then I became interested in actors because I denounced my creative search and searched my actors instead. This became a great adventure: the discovery of a human being. This was very mysterious. It was a great surprise, unforeseen.

At the precise moment when the human actor was creative, he penetrated unknown terrain. If this is really unknown, it requires great mobilization, all faculties, energies, joy of risk, great skill, great curiosity, all these are required to penetrate the unknown possibilities. Habitually, the actors would say, “I cannot do this. I’ve never done it.” But in reality, the actor is creative; he does penetrate the unknown. This moment of curious exploration is like the gratification of nature, in that it produces a form of expression. One who really penetrates the unknown space is surrounded by a halo of space. This is where the actor’s danger really begins. Later, on a different day, to penetrate space again, he repeats the known and fails. Or he might just lunge again and again at the unknown, bouncing up and down like the flight of the chicken. Here is the way to real beauty: at the beginning, he does the known, the first steps. It is not like a real flight, but across the runway. He sometimes discovers at the end of the runway some very small part of the unknown. It may be only a very minute detail, but once engaged with this, he moves in a way that is other than known. He remains in connection with the unknown because of this little unknown. We must remember this little unknown to find the values of the immediate and present.

In the past, when we did the exercises, we started by demolishing the known systems of training. I have described this in my book, Toward a Poor Theatre. In many parts of the world people have used our exercises in the opposite sense. We have always sought to untame the body. They have used the exercises to tame the body. This is very annoying to me. This is the same with Stanislavski. He understood the things that I speak of. In the last period especially, when he was working on the method of physical actions, other research, aside from theatre, he really discovered miraculous things. But the world used elements of his work in opposition to his ends, as tricks or gimmicks. With Meyerhold it is difficult to know. There is very little precise information on his biomechanics, but I believe (little as I know), that it was a pragmatic technique to achieve a desired action by moving along a short-cut, a theatrical tailoring. In reality his greatness is not in biomechanics but in other things. Biomechanics was not essential for him, but secondary.

At times I have seen real things in rehearsals that could never happen in the performance: moments explosive with the immediate when we forgot what play we were doing, what space we were in, what day it was, what time it was. Present time and space and our presence became flames that engulfed us, that devoured us. We had to ask ourselves if this could possibly happen with people from the outside. No, we were not naïve enough to try to create the participation of the spectator in the performance. We had tried this in 1959 and 1960. It worked well from external results, but denied human truth. Clearly the devouring immediate is not found by the accidental means of buying a ticket, etc. There must be a selective means of finding each other. People say this is not democratic. This is very amusing. If you behave as a pimp: “These are our attractions, buy us, buy us!” Is that democratic? To seek each other with common needs, this is called undemocratic. This is mysterious, but the way it always is.

We needed a way to encounter each other in a common group with devouring immediacy. It was at this time that I saw that all artifices were unnecessary for our purposes. What I realized is this: it is absurd and immoral to cut part of a living tree and put it in our theatres because we like trees. This is very simple. Go to the earth, do not bring the earth to you. If you need the trees, if you need the night, then you go to them. If you need city space, go there. If you need uninhabited space, go there. If you need wind, go there. We like children, but do not cut their heads off and put them on stage.

Because of these things we abandoned the theatre building. We took from it the things that we liked: the devouring immediacy, the little group, selected according to mutual needs. We took these and look for them now where they are, not creating them artificially in our space, but creating ourselves in theirs. This is paratheatre. I realized that to follow this logic, I must engage in this new adventure. What would come of it was unknown. At that moment when we started this thing, it was also inevitable that we could only contact small groups – we could not reach the masses. For a number of years, 1970 to 1973, we included only three, four, or five people at a time, no more. I had no vision of more people. I knew no other vision. Small groups – that was all I knew, that was all I witnessed. If I had hesitated then because of the paper tiger of the future, I would have announced to all of you, “You are crazy! This will fail! This will go bad!” How can you lead a great art institution this way? You will be fired. You will never be popular. I thought this was true. I feared it. But I did what I had to and this taught me how to open this for more people. After, thousands of people passed through it. It happened. It happened when it could happen, not too soon and not too late. My intellect told me to abandon it all. I would have lost the future. And now, after many years, we do involve many, many people. More people are involved all the time. There was no way to know this at the time.

There are many reasons for doing theatre. You may do it for money, or you may do it for social status, but these are very suspect. Working with your own body, leaving your body open to buying and selling, this is very embarrassing.

In France, Italy, Spain, and Scandinavia currently there is what is called “The Third Theatre.” This is social theatre. To live in a certain way, one must meet others, and theatre groups offer a good opportunity for this: to arrange new ways of living. It is inevitable to want to incorporate this into a larger society. One needs a justification to be what one is. Theatre is always a good pretext. It is said, “Artists” – especially actors – are weird and strange. It is acceptable and unthreatening to society at large to live this way. It is even acceptable to society to do this and to ask for help – to negotiate with society. But there is another reason for theatre, a third aspect. In the third aspect, a group meets to share a way of living, but the group must have concrete work or all will find the work stupid and the group will disintegrate. Work in theatre is a concrete thing. A group can be based on this; it is healthy and good.

This is the way the Third Theatre Movement is: this is theatre as a justification or pretext. This is apparent everywhere: theatre as mental health or therapy. For example, a Hindu goes to a far off unknown temple. He removes all his clothes. He sits in the middle of the street or on the bank of a river and goes into a catatonic state—a trance. In our society we call this behavior sick. We ignore the fact that by repressing it, we cause catastrophe. But what he does is very concrete. In India, after years in this trance, the person is fulfilled with great knowledge and power. The result is not catastrophic at all. The way this happens is correct in the context of Indian tradition. It is not sick. His behavior in our world is sick; the context and tradition are not correct. In our civilization, must he renounce the world? No. He must, instead, find the right pretext. Culture is really very free ground and therefore is the context of our civilization and for growth in it. The people of the Third Theatre are an example of this. They confront their own needs with social needs and they find a balance where they live, without mortal confrontation.

Other examples of why theatre can be done: a trip to learn our own nature, the nature of things—confrontation, tangible and carnal, with the self. There are many other reasons to do theatre than merely to be “professional”. Groups exist, whether professional or not, which seek out the human quest. I don’t propose that others follow us by the same route or passage. Some must do something analogous, if they need to, but this is only one of the many reasons or solutions.

I think now we must “split,” or divide, if you have other things to do. For others, there is a twenty-minute intermission, then more questions. And also, I propose that others of you analyze this in your own way, argue, or say important things. It is not important for myself or others to say things; it is important that things are said.

20 Minute Intermission

Grotowski: Before continuing, I wish to make two clarifications. I fear there may be some misunderstanding from what I have said. First, what I mean by the idea of “professionalism” is not the same thing as professional theatre. Amateur theatre can be guided by the idea of professionalism and professional theatre can be guided by another idea: for example, Stanislavski’s Moscow Art Theatre. This theatre was professional or even supra-professional, but it was guided by an idea of creativity, an idea of art shared with the public, a coming together of audience and artist. It was guided, in other words, by a moral ethic that was very high. In our time, throughout the world there are professional theatres that go beyond the idea of “professionalism” that I speak of and are more than that. The idea of “professionalism” I speak of is simply to treat art as a money-making activity. Commercialism may be a better word.

Grotowski: Before continuing, I wish to make two clarifications. I fear there may be some misunderstanding from what I have said. First, what I mean by the idea of “professionalism” is not the same thing as professional theatre. Amateur theatre can be guided by the idea of professionalism and professional theatre can be guided by another idea: for example, Stanislavski’s Moscow Art Theatre. This theatre was professional or even supra-professional, but it was guided by an idea of creativity, an idea of art shared with the public, a coming together of audience and artist. It was guided, in other words, by a moral ethic that was very high. In our time, throughout the world there are professional theatres that go beyond the idea of “professionalism” that I speak of and are more than that. The idea of “professionalism” I speak of is simply to treat art as a money-making activity. Commercialism may be a better word.

Secondly, it is very important to be properly understood in this. If I do something, others should not merely imitate me. Real culture is always manifold or it is threatened and stagnates. One must understand that human beings are different. Human needs are different. One must look at and believe in one’s self and one’s own culture in this way. It is wrong to say, “I do this, therefore I believe.” It is right to say, “I believe and therefore I do it.” Others have, I know, other needs. All I say must be understood in the context of manifold culture. I would fight what I do if I thought it the only way. In this case it would oppress others and become bad. In this way ritual plays no part in what we do. It is meaningful only to the parts of culture that are concerned with the analytical. I am concerned with the creative. More questions, please.

Question: What are the strengths and weaknesses of choosing this path of movement? People come away with something from this work. They have been affected in some way, but perhaps our culture suppresses this. How can we use this in daily life?

GROTOWSKI: Can you only search for your actions with us or can they be found on other paths? Our objective – that word is bad, but – our basis is very important for human beings. We do not have exclusive ownership of what is important to human beings. Many are searching for these things. They are here and everywhere. There is no owner of the essential. It is shared by many with access to it by many different roads. I give the example of movement, but it is not found only by movement. Only my example is movement. What is perhaps important are questions; for example, you have asked an essential question. In order to live in a community of men, we must learn in theory only one role. But in reality we must play many roles. Here, there, work, play, family, etc., the fact of having to play roles in life is not good or bad. A role is a kind of language. It is connection, a way of people meeting one another. Two people meet: what is the first question? “Who are you?” Answer: “I am . . . “ the answerer has said something; he has not said nothing. But he has not really answered the question. If he thinks he has, then he has lost himself to the role. You must not identify with the role or you cut off your source. The essential problem here is that it is not an actor playing a role, that concept is wrong. It’s a man, alive, trying to contact other men, alive. You ask me how you can find obvious, natural opportunities. Surprisingly, this question is not uncommon. The one wrong way to do this is to renounce acting. In this case, you “act” the role of being free. This is one of the very worst roles: this is being a “junky.” For these reasons the suspension of role-playing will always be a failure.

True suspension of role-playing is dependent on that which is evident. One should not say, “I don’t play roles.” All you’re doing then is playing the role of “being free.” Find the circumstances where daily play does not function. Then play whatever circumstances are obvious and evident. When you know the experience outside the play, then you know afterwards when you are playing. You will accept roles more comfortably and in whatever way the situation demands. For me the key is to know how to do nothing, really nothing.

By no means begin with movement. The “idea” of movement leads to producing movement, and then you have future, conception, etc. Tell yourself, “Don’t do anything.” You get embarrassed. This is the best illusion: doing what you want to do, until it dies. If, when you want to sleep, but there is no opportunity; when there is confused silence and you don’t speak; when you don’t think something must be done, then: reality. You don’t think of results, you know there is nothing to do. Immediately something starts from nothing—everything becomes . . . as it is. Someone sits in a certain way, not thinking of what this means to others, but only for his body’s need. Someone is sleepy or hungry or plays an instrument. These are the first true moments in this experience. Playing instruments is the same. One eats, sleeps--eats wanting to eat, nothing else. He does what he does. In this moment, one plays the instrument in the same way: simply to play, for no other reason. This is the important moment when the experience really happens. This is what I mean by the movement in the forest in the night, or gravity as fuel. This is the moment when we arrive, we are in the immediate. This situation happens through the power of itself. You drop all gimmicks of daily play. This is more simple, elementary. It is nothing—like the movement of a bird in the air. What is this, in reality? This is to rediscover and find the simple, the obvious, the evident.

This is not found through silence. Silences speak more than words, but can be bad, another form of conscious manipulation. False meditation, psychic narcissism, these are all part of the search for the exceptional moment. But, really, what we value is not this: the exceptional moment. It is the original – the original – something we knew but forgot and betrayed. But this is the most simple and the most evident. It is true.

In modern civilization, especially if high technology has developed, high commercial pressure and the success notion make us do what we hate – “for the future.” This is true, and one must not begin screaming, “Change civilization,” because that doesn’t change anything. One must surpass the civilization’s limitations, but stay within it. Learn to manage in it, but be careful – for it’s very important – if one doesn’t manage and complains, he becomes the slave of civilization. He is led by civilization like an invalid. You must know how to manage to live in your own way.

The moment you asked the question: “The participants, how can they use what they gain from this work in daily life?” you touched at the same time something important threatened by civilization. You are saying that something must come of this, like therapy. The people who experience this should be less neurotic, or less shy. This is not right. This is not right. It is under your feet and in every moment. If you discover this, only for a moment, what comes of it? It’s only the moment, only the hour, so it has no value. Exactly, one or two hours of something has value. You must accept what has no objective, then you start to have a chance in life. You lose those traditional fears which come from the future. If I think that death is fearful and if I think of it all the time, I lose my life.

Question: At the moment only a very few people have managed to participate in your new work. Do you have plans to open this up, to reach a broader audience?

GROTOWSKI: Should we reach broader audiences? Yes. The fact that the total population isn’t involved is evident. But it is a wrong and false idea to involve everyone. I hate the word ‘culture,’ but if you like it. . . This is not obligatory, an obligatory experience, like elementary education. One should not want to involve everyone. In general, those who come and involve themselves with us are not part of the theatre milieu. Professional theatre people are the smallest percentage of people who come to us in Poland and other countries. But if the professional theatre people come for this, we would accept them.

A small segment of our activities involve theatre people. It is called actor therapy. This is the unlocking of the voice and the body. This is parallel work to theatre and also to our work. But, of course, this is not only for actors. Many people use their voices; for example, a teacher uses his voice like an actor.

Why is this named acting therapy? This aspect of our work is a discussion of the maladies of a profession. We said we are not interested in the illness of people, but of the craft, in this aspect of our work. What we want to do here is to heal the maladies of the craft. We are not interested in healing the maladies of the self, and so it is therapy in that sense.

On the other hand, our main activities involve many people. The Third Theatre people, or student theatre people, or this type, are very numerous. But one must not generalize. There are many ways of approaching the work for this group or for that. These experiences are very different for each group. Perhaps the differences are like circles in a pond of water.

In approaching the work, it is not a problem of being open. He does his best imitation of an American accent. “You know, buddy, I have a big problem.“ General laughter. What is the problem? One need not try to be open. This is very wrong because to be open . . . Warmth is alive and has its own force. You know, often the most cruel people are the most sentimental. To be open is not wrong. The problem is in the conceptualization, in the first approach.

What I am talking about is simply to do that which is evident and nothing else. The farther along you go, the more difficult it is – not from fatigue, but in the fact that you can’t find it if you look for it. One must follow chance. This is what is original, primary. Where does my body begin? Where does my body begin? Pause. Where does my life begin – now? There is something that is always after: the gestures, fears, satisfactions I have learned. But there is something before that – like the moment you awake naturally, not from an alarm clock, not with the idea to do something. You open your eyes, you don’t know yet what you are. Before everything comes to you, you know nothing. You emerge into life – where from?

Question: What is the difference in Grotowski’s work in meeting and in looking at a painting?

GROTOWSKI: To be honest, I don’t know.

Question: I am interested in how you approached your production of “Shakuntala.” Can you tell us something about this production—describe it?

Question: I would like to know something about your background in theatre. Have you had any formal theatrical training? Can you tell us something about this?

Question: In myself, I feel a constant conflict, what I call a spiritual war, between the eternal, spiritual side of life and the temporal, physical side of life. What about death? Is Holiday a sanction against death, or an avoidance of it?

GROTOWSKI: At the end of the ‘50’s and the beginning of the ‘60’s everyone in the world theatre was talking about theatre as a means for social confrontation. This was, at the same time, very idealistic and pragmatic. It was idealistic in the sense that theatre existed to change society, and pragmatic in that people only talked of the means. At that time I talked about the spiritual because of this context.

In the second half of the ‘60’s everyone spoke of the spiritual, of human potential, of metaphysical things. At that time, following this, I was engaged in a workshop with five directors from different countries. I was shown a dog controlled by the telepathy of actors. Everywhere I fought the temptation to do yoga in ten lessons and to do Zen in three-day lessons. And then there were the consequences of Castaneda. Everyone started talking about the unreal. This was important, but it is not resolved through sentimentalism.

One day I was invited to contact a tree. People caressed the tree. They said that they had experienced great emotional states. I believe it well. Laughter. I also believe that it is possible to contact a tree, but not in this way.

I began to speak about the body. The human being cannot be divided. It is only the intellect which tries to polarize, to divide the human being. We talk about body and soul. Scientists divide the human being between the intellectual and the sexual. In the ‘40’s and ‘50’s there was the notion of the enlightened man. The intellect was the summit of man. If one is tolerant, one accepts the Freudian version of man: the sexual. This is even found in Sartre. But there is an enormous space of other faculties between the two: a space that is extremely vital for the human being.

For the spiritual to be immediate, it must be tangible and therefore corporal because if one abandons this carnal aspect of man, one falls inevitably into a confusion between the spiritual and feeling. Feeling in this context means nothing. With this clarification I agree with your point of view of the spiritual.

This holy day, or holiday, was the word said one day. It has no importance in itself. ‘Immediate’ is another word. This is the first time, today, that I used it. In order not to be automatic, I impose on myself to speak about the essential always with new terminology.

You are right that this notion of inevitable is something which decides everything. If you speak about death at a certain age, it is sudden – not always, but often. There are things tied to death that are more annoying than death itself. Currently, for many, it is the monstrosity of old age. The body becomes unacceptable. In Simone De Bouvoir’s book The Coming of Age, she talks about the skin, the knuckles, how ugly they are. It was very emotional to see how she talked about these things. She is often very artificial, very sophisticated, but in this she was very touching.

Someone makes a career according to the rules. He assumes social positions, he has reached certain levels, and he begins to realize that it is time for the young to attack. He cannot advance further, but he can be abolished. Others come near him who are more dynamic. They must be manipulated, kept at a distance. This is not a struggle to advance, but to stay in place. Finally, at some point in time, one must leave, hating the successor. One has ten, twenty, thirty years more to live, a second life. But it now makes no sense. What can be done?

Yes, if one accepts a certain way of understanding life as a game of competition, the second half of life is a garbage can. But if you seek another sense in life, without the protection of going toward the future, the second half of life is a very interesting field. You are not afraid of the successor. You look for him. This is tied with death, with the inevitable. If you look into the eyes of the inevitable, this makes a difference in everything you do. It is not an escape. You throw into the game of images something that makes life evident.

Ask yourself, what evident things do you do every day for yourself? You do things for your parents, for your friends, for your teachers, or against those things that are evident for your parents; but what do you do for you? This appears when you look into the eyes of the inevitable. I don’t like the word ‘spiritual’ because of confusions with this word, but I don’t mind someone else using it.

One must not think of an answer to the inevitable in the category of holiday, meeting, or workshop. You have a workshop and then what? One must try to rediscover the occasion in order to experience the evident. Workshop is only the name for a structure which is socially acceptable. It would be stupid to change your life from the experience of the workshop. On the contrary, you should seek something from life. One seeks certain circumstances. One of these occasions is a workshop.

Question: Have you been influenced by Copeau in your work?

GROTOWSKI: I know very little about Copeau but I have been told that I should know more.

Question: Can you tell us something of the dialectics of your new work?

GROTOWSKI: For the moment, I only want to underline that when I’m sincere – I wanted very much to be sincere this evening – I’m not brilliant. When I am sincere, I have no theories. I could not care less for theories. I make an attempt to pass something I know by experience.

There are times when I speak theoretically. If I find I cannot say anything really, that no-one will understand except as a social game, I turn on all the dialectics necessary. I invent a logical theory. In that case, I am brilliant. Laughter.

I understand that this sounds like theory to someone listening because it is verbal. There are certain questions that I have not answered. Those who have asked and not been answered, return tomorrow evening at eight o’clock and I will answer. I am very tired, fatigued, and I fear that I will put the intellectual machinery in gear. I propose to you all to come at eight tomorrow in a very precise frame of mind. If there are among you some who would like to share an experience with us in Poland, come tomorrow and we will speak of these needs and so on.

SECOND SESSION - November 9, 1977

GROTOWSKI: Last night we talked for six hours. Tonight, hopefully, things will go much faster. We will start with the questions left over from last night. This will be our schedule: first, those questions, then, new questions, and then I will outline opportunities in Poland. So I would like to ask those who asked questions last night to repeat them.

GROTOWSKI: Last night we talked for six hours. Tonight, hopefully, things will go much faster. We will start with the questions left over from last night. This will be our schedule: first, those questions, then, new questions, and then I will outline opportunities in Poland. So I would like to ask those who asked questions last night to repeat them.

Question: Can you tell us something of the dialectics of your new work?

GROTOWSKI: I have answered part of this question, the part about dialectics. But I have not spoken to the idea of story. Obviously, performing confronts the idea of the story. I think fable may be a better word. This is inevitable. Even when you try not to make a story in performance, if there is a division between the actors and spectators, then the audience will look for a story. If there is no story, the actors lose the audience; they lose their attention. The audience will invent a story and the actors lose the audience; they lose their attention. The audience will invent a story in this case, at best. They will invent one that is confused and wrong and may have nothing to do with what the actors are doing. So it is better, even if you yourself are not looking for a story – when you mount the play, at this time, you must think of the story. It may be very simple. Something goes on, something happens. It has a beginning; it has a middle and an end; and at moments, it fulfills these needs.

Of course, there are different approaches to this. One approach is to show a story from somewhere else. For example, the space where the actors perform and all their actions refer to events that took place elsewhere. This is what happens in classical plays: “Hamlet,” for example. This story happens somewhere else – maybe in the mind of the writer – but not if it is re-realized here in the minds of the actors and spectators. Personally, from the very beginning of my career this approach repulsed me; there was nothing in it for me. Another person who used this approach, such as Brecht, for him it was right. I approved of it. For me, it was not right – no.

I looked for other possibilities, even in the classics. For me, another idea of story became important. I wanted to know about the story that is happening at the moment of the performance. I will give you a specific example from my work: consider my approach to “The Constant Prince.” There are voyeurs in life: this role is played by the audience. The entire space is therefore arranged to suggest voyeurism by them. What happened was, in actuality, an act by my colleague, Ryszard Cieslak, the actor. This was a human act of Cieslak’s, done in the presence of voyeurs. But it was independent of them. It was an act of renouncing himself to himself, of reducing himself to the prime truth of human existence. The act took place on two levels for the spectators. One level was a story of this moment, in the present tense, here and now. The other level involved historical and literal associations of the story. Our version comes to us through the Polish poet, Slowacki. So, it was a story from Medieval Morocco, told by a Renaissance Spanish poet, retold by a 19th century Polish poet, and performed/retold by 20th century Polish actors.

On one of our tours we took “The Constant Prince” to Iran. For one performance we invited people in off the street for free. We had found a space in a poor and illiterate neighborhood. They had no idea of the theatre; they had never heard of Calderon or his story of Prince Ferdinand. They didn’t understand Polish.

I was stunned by the people’s reaction. It seemed there was a frightening resonance of this story in them. They screamed, they cried. I didn’t comprehend their reaction at all. Afterwards, in talking with our friends in Iran, we learned why they reacted this way. In Iranian Islamic mythology there is the story of a prophet. He is Hussein, the son of Ali, who was martyred: he was persecuted and tortured to death. His enemies did this to him because he would not renounce his truth. This story’s influence was strong enough in these people’s lives so that they understood our story through their story. Or, let us say that they saw this other story. But I believe that this enigma, this mystery was possible and happened because we did not play the story of Ferdinand in Medieval Morocco but of Cieslak in the present. For us, all that we did was the immediate truth.

The story by itself, if it is the story of Hussein the prophet or if it’s the story of the Constant Prince, whichever is more familiar to the audience, that story has no importance to us. The only thing that is important in this respect is that it is better to know which story the audience is going to invent, rather than to confuse them.

In our situation, the situation of theatre, even if we say that there is no story – I will not tell a story – still, the person watching, the spectator, will invent a story. This is from the force of the situation: the power of the situation. There is one who watches – the spectator; there is another one who acts. This one who acts, he moves. “Why? Where?” The spectator asks questions like this. In some ways the story seems almost unimportant. The only thing that is important is the act. But while mounting the performance, it is preferable to think of the audience’s associations with stories and fables. By “mounting the performance,” I mean editing the piece for the time of performance, for that moment, not before. To anticipate the audience and their story, this is wrong. To search for it in rehearsals, this is wrong. And so we tried to reduce the accent on story.

On the other hand, if you drop the story, a situation will emerge in rehearsal: a new story will occur. This will be our story: the story of human beings who do something: something happens between them. This begins; it has a middle and an end; presence is felt even more when it is not sought out. In this story, you pass from performance experience – being actors and audience – to being participants.

This is a big change, but it came from a small change, if you think about it. Personally, I believe this is an important restructuring. It is artificial to search for a story; that is the easiest way to kill present time. But of course, in the second sense a story will always appear. It will be our story. It will take place in that time and space. It will be the story of our life. Every moment we live, in one sense, is a story. Our memory makes it a story. One can mark the moments of it: the beginning, the middle, the end; and so it’s a story, but only afterwards, in the past tense. This is artificial. Life is not a story while it happens, and I am much more interested in life than in a story. New question, please.

Question: Grotowski is playing with semantics when he rejects the word ‘spiritual’. Is he saying that we should not worry about death because it is part of the future? I think we must know death to know life.

GROTOWSKI: Help me to understand your use of the word ’spiritual’. Explain it in more detail, please.

Question: It is a projection of life into another mode of existence, a mode other than physical: the eternal.

GROTOWSKI: You speak of projection, but what is projected? From where, to where? From the temporal to the eternal, or maybe the other way around? Is it total personality? Is it your personality going into the eternal, or the eternal going into your personality? Where does it start or end? From here on? You have said that death is in the present, not in the future. Tell me, is there any difference between your present state and the state of a coma before death? What is the difference? I believe there is a difference in life between these states, but not in death. But this is not the question. Is death here the unknown? Or is death here the future – an event that happens in the future? This is the question.

I hesitate before metaphors; I do not like them. They confuse as much as explain. To say that death is present always, as it is at the moment of death, this is a metaphor. The metaphor is an intellectual trap.

On the other hand, when we speak of the difference in life between these states, this I understand. But all these are problems of personal preference. The only difference between us is a difference of preference because, when you’re dealing with these questions, when you touch the ultimate, such contradictions disappear. They all evaporate. There is no right or wrong answer to these questions. Death, eternity, etc., these are not questions with answers – they are facts. Perhaps one can claim his preference is true, if what he believes is what he lives.

If you wish to speak of preferences, I will tell you mine. This is what I say: do not speak of ideas, or even pronounce the words such as ‘eternity.’ In one sense I think there are two worlds that exist: two worlds of human life and experience. One is our human world created by thinking and interpreting. This world gives us the illusion of comfort and security. But there are other worlds that exist too. This world that is a product of human creation is a product of the mind and interpretation. It is not eternal, but it is older than us; it survives us. Secondly, there is the world as it is. This is a very different world. It is almost the opposite of that imaginary world of comfort. It offers an opposite experience. Can I touch the world as it is? Yes, and the way that I do this is to touch myself as I am. In this moment I can have the experience. Afterward my memory and mind take over; they take this experience and use it to invent this world again for human beings. The mind turns the real world into the imaginary world.

Now this second world, the world as it is, is this the prime, original world? Is it the eternal world? All I can say is that that word ‘eternal’, and others like ‘spirit’ and ‘spiritual,’ those words are invented and belong to the imaginary world of comfort and security – the first world I spoke of. If I look for words, everything I do will always be invalid. I am condemned to use them because I am condemned to say something about the not-human world, the world as it is; this is the acceptable way to pass something to you, to communicate. The world as it is: this is the world of stars, the world of trees, of water; and I say this with words. I can touch this world when I am as original as a tree, or a star, or water. But to say this makes this invalid. It is not exact.

You look at someone, a human being. Maybe he is a person who is very exceptional, maybe a very great person, and you think that person really touches the spiritual. But what do you see? You see what is present, and that is his body. The only way you can tell what you call spiritual is by what you call physical. The body bears witness to the spiritual. You have not met the spiritual if you have not met the body.

I often think of Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha. Siddhartha looks at Buddha and this is how he achieves enlightenment. He ignores Buddha’s sayings and teachings. He looks at the way Buddha moves his fingers, the way Buddha watches others, the way Buddha stops, and Siddhartha says, “Yes, this is a perfect being.” This encompasses my personal preference. The spiritual is always in rapport with the tangible and carnal.

I will tell you a story of a young Belgian. He was eighteen year old in 1972 when he attended The Conference of Serenity. Learned men, psychiatrists, psychologists, of remarkable talent and great reputation, from all over the world, organized and attended this conference. They spoke of serenity at great length, in much detail, with great insight. Among them was a seventy-five year old Swiss psychologist. This man said very little. After the conference my young Belgian fiend went to the old Swiss man and asked to apprentice with him. Five years later, I was speaking with this friend; I asked him why he had done this. He said that of all the people at The Conference of Serenity there was only one serene person: this was the old man. I asked then, was the old man a yogi? The young man answered, “Apparently, yes, but that word is misleading. Most people think of yogis as supermen, that they age without losing their life, or looks, or vitality; that they are always fresh and never tired. The old man I’ve known for five years has aged very much. When he sits now he has trouble rising; he trembles; he cannot walk far, his hair is falling out; his skin wrinkles; but his body always speaks to me and tells me life is full.”

This is not a polemic; I did not mean it to be so. I am only stating my preference. The difference in our points of view is unimportant. This is not a situation where it matters if both of us are right. Both, in a certain way, can be wrong, but I hope not. In some points I know we are not wrong. Next question.

Question: When Grotowski was working traditionally, how did he find the traces of the immediate? Can he give us a specific instance?

GROTOWSKI: In this period of my work, if the immediate appeared, it was crippled like an invalid and always so very weak. This makes the problem of a specific example even more difficult than it is for the problems of speaking of the immediate that I’ve told you about already. In addition, an example must be elementary. One example that was constant and growing for us was in our movement. Through our movement we realized increasingly moments of the immediate in our rehearsal and in performance. But this is not specific enough, I know. I will give you something specific that I am inventing – actually, just enlarging on.

There was a place in a play where I wanted something done. I wanted something to be as a farewell to the house of life and security, the house of the protected life, the house where a person is protected from the blows of life. I searched very long and hard for this. I thought that it must be constructed with a visual metaphor, this farewell to the ‘wigwam’. A song of good-bye, I decided, was what was necessary. I wanted the melody and the words to be just perfect. Of course, the visual metaphor was dead already. It is dead because it is only a conception. The most that can be done with it is to narrate the past. It cannot bear witness to the present. By relying on conceptions, all I was doing was building new wigwams. I would build them for the actor and thereby provide him with an alibi for not making a wigwam of his own. This thwarted the entire purpose of making a wigwam for the present, with our own presence. The only responsibility I left him, his only action, was an automatic and technical ‘duty’. He must memorize my song. How boring!

One day, however, my actor went through the motions of constructing my wigwam, came to the proper moment, opened his mouth, and could not sing. Catastrophe! It didn’t work! The melody was rotten; the rhythm was all wrong; it never worked again. Catastrophe! Now I had a new problem. What can I do with this actor? How can we find this song again?

The actor and I meet together. It is late; everyone else has gone home. Together now in this space we begin to search. I had looked with him for something that had meaning for him. Perhaps first we find souvenirs, reminiscences of his past. At some time in his life he has had to say goodbye. A souvenir of this experience is carried in his emotional memory, his emotional luggage. Yes, he says, I remember such things. “What did you do at these times?” I asked, “Do this for me.” And so he does an imitation of the past, in an improvisation. More or less, it is realistic. Now our task seems clearer. All we must do is make the past the truth. But the truth of this belongs only to the past. The truth of the present is not a song of farewell, as I wanted, it is only in half successful efforts at reconstruction. This is not the thing itself, this truth, but it is better than nothing. It gives me a way to work, on which I can proceed.

I give him another challenge. I seek, without formulating, to push him toward present awareness, to say goodbye to the things that at this moment he is saying goodbye to: I mean the things of his life, of this moment, things he knows he must say goodbye to, but is not admitting it. There are things that everyone has to say goodbye to always: for example, to youth. Until we say goodbye to youth, we cannot accept age, and so every minute we are saying goodbye to youth because we must accept age, we have no choice in the matter.

I try with this actor to put him into a situation where he is saying goodbye to this – to let him discover this. I tell him I don’t want to know what he is saying goodbye to until he says goodbye. We will not kill this goodbye by verbalizing, conceptualizing, formulating. When he is ready to say it, then he must say it. Before that it must be unarticulated. When he says it, it may be however it happens; it must find its own form: a touch, a look, whatever. The moment comes. He finds his goodbye. I see him arrive. I see the moment that he stops all his effort to express. I see this because there is a moment of nothing. His body moves invisibly and any way, but he does nothing. He turns around, leans over, and sings quietly; he sings some non-existent melody. He sings absurd words. This is goodbye. I am embarrassed because I loved my wigwam so much, I worked so hard for it, and now I know that it was exactly the wrong thing to do. My wigwam has been removed and eliminated. I drop my song because he has found what belongs to him: something that is evident in that moment of his life. This rose out of the moment of nothing. It could never rise out of my inventions as a stage director. I know this now by following, by searching for moments of nothingness.

Question: Where does Grotowski fit? Is he trying to find his own place, or a new place in traditional theatre?

GROTOWSKI: A tradition is either alive or dead. If it is dead, bury it and let it rest in peace. It is grotesque to carry the dead about with us. On the other hand, if it is alive then it belongs to our life and is a part of us. For example, the poor Iranians who saw “The Constant Prince”: the traditions of this story were alive in them. They reacted to it from the force of living tradition. If what you do is in rapport, direct and simple rapport with life, with the things we know and the things we don’t know about life, then the living tradition will appear. It is so inbred it will appear because it lives. It appears if we do the things that are acts of our lives. Unfortunately, we are tempted to only realize the conceptions, artistic ideas, the sort of paraphernalia common to the imaginary world of interpretation. All we do is illustrate conceptions, and afterwards, to find the roots, we take books and study to find bridges between our memory of our lives and the larger memory of this traditional imaginary world. All we are doing is connecting conception with conception. It has so little to do with the world as it is. To do this is to destroy real tradition. In this world, this false world I’m speaking of, when we must verbalize, we are not sincere; we are false. We artificially produce words of and for and about an artificial world. If one does an act of life, all the roots are present, whether they have been looked for or not.

Question: To be devoured by present time . . . to only be in the moment . . . My experiences in paratheatre . . . it’s so hard to return to the social contract. It is so different from our lives—from our life, which we discover in the work, in the experience . . .

GROTOWSKI: To others in the audience. No, no, I understand what he is trying to say, let me answer him. I do understand, I think, what you say. This is a good example of what I mean when I say verbalization kills the experience. I prefer not to talk of it entirely, but the social mode condemns us.

Of what you say, there is one thing which I can speak of, which I must speak of. I must make it clear. The social convention is repressive, this is true. But, also, these social conventions make our life possible. For this reason, I prefer not to deal with the social convention as an enemy, but as a simple circumstance. I think it is very important to learn to cope. If we can learn to be at ease there, if we can learn to be at ease then, even though you may not have the heart for it, as with myself, it still can become acceptable. This is the only way that you can get free of it. To make yourself an enemy of the social conventions, you both revolt and submit to it.

Say you are in the process of leaving your space. You live in a house and at a distance from the house there is a lake, a beautiful lake with the sun and the moon reflected in it. You have left your house and are going to the lake. Between your house and the lake there is a swamp. If I care too much about the swamp, if I hate it and make it my enemy, I forget my house, I forget the lake. I am lost to fear. I get lost in the swamp and I drown. If I had never feared I would drown, I never would have drowned.

On the other hand, if I treat the swamp as something usual, it is very different. The swamp, you see, is always as large as I make it. I know it and treat it with respect. I step where there are tree roots, where there are rocks. Soon I love (have heart) for this jungle. It is my jungle, my swamp. I am safe in it, whether I lie in it or run through it. Perhaps I have renounced the lake. I have my house and jungle. But if I keep the lake in mind, if I make the jungle my ally and love it, then it helps me get to the lake. This is the best way for me when dealing with the social convention.

Question: Much of your language is similar to the language of Zen Buddhism, Tai-Chi-Ch’uan, etc. Did these influence you?

GROTOWSKI: It is very difficult to know what really influences us. Sometimes something may have no tangible reality. It may be just an intellectual game; this can influence us. In other cases, perhaps, influence may be very precise. This man touched us in this way; this act happened at this time, etc., etc. The influence is the same whether we are aware of it or not.

On the other hand, the influence of life, this influence pours; it flows through our bodies. Perhaps this is the only real influence. It is certainly the most important. Unfortunately, this influence in all of us was denied early in life. What resulted was a catastrophe, a kind of amnesia. If one blocks the influence of life, one forgets it. In this case, you lose the ability to meet people. If you do meet people, it is by accident. You must find your own life’s influence. From this you gain a kind of knowledge. Perhaps you discover that others have searched for this knowledge also. In fact, if others have not searched for it, perhaps it is not real.

The way I found this influence is this: I was discouraged, I was desperate. Life seemed empty and worthless. I gave up, and poof – I found my memory. For a second, amnesia ceased, life appeared, and its influence reasserted itself. What is awful, terrible, is that, at that moment, you start to kill the moment yourself. If one speaks of the simple, the original, the intimate, it is not obligated to be beyond the oceans, above the seventh mountain range. But I understand if maybe someone must go there to find the memory that I speak of. This influence of life is the most intimate influence of all. It is not even a memory; it is a fact. It is the fact.

Probably these examples of different possibilities have had influence on me, but it has been only limited influence, only influential on what I think, on what I say; I know them for this reason. If I think about it, perhaps I have answered too strictly about Zen and Chinese techniques, about which I know very little. I did study some Chinese theatre, but I don’t know if the principles are the same. About Zen, let me say this. There is much that is very fascinating. In certain texts there are some things that are miraculous, and much in reality that is wonderful. The notion of simply sitting: simply to sit. If someone is worried about his computer, his brain too is worried, and it is like giving a bone to a barking dog – to give him a ‘koan’. The ‘koan’ will calm him down. It takes all his worry about his computer away from him and reduces him to the essential. It teaches him to sit, not in a special way, but to be present in the body.

I don’t have enough patience for that. I admire it greatly from the outside. Perhaps in some ways it may appear similar to what I speak of, but I think only to people who know neither. In the Zen method there is perhaps a certain perfection that embarrasses me. I need to go and sit down. In most situations this is obvious; it is evident. To do this when I need to, this makes life very full. The sitting in itself is not full, but it provides the occasion for something very full. You feel very small, no great pride, only small. Again, you sit in the present. This is a great occasion. But in Zen it is more perfect, and perhaps you are to know things in Zen of which I know nothing. I admire the simplicity of Zen, but I don’t feel at home with it.

When I read Jack Kerouac’s Dharma-bums, about Gary Snyder and Zen, I began to understand Gary Snyder’s book, Earth Houses. Clearly, for Snyder, Zen is what carries him. I remember how Snyder teaches Kerouac to climb mountains. Snyder tells him what to do with his legs. He says, “Leave your legs to work their own way. Only look ahead, go where you are going.” This moment is very close to me. Whether it is close to Zen, I do not know. That is all.

Question: Can you define your concept of passive readiness for the actor?

GROTOWSKI: In the work of the actor, yes. Pause. Shakes his head. The example of my colleague singing goodbye: when he found the train of how to get there, the way the hunter finds a trail, he found himself in the intimate situation. In the everyday world it is most natural to refuse this; it is too intimate. If he said, yes, it is too intimate, but I am the actor, it is my job to express my intimacy, he will mobilize himself to do that. He will work at doing that. Already, he has lost it. He will not find it through work. He couldn’t understand me until he found his trail. I saw him struggle; he tries this way and that way. He hears my words but he does not understand me. He is very uncomfortable; he feels very bad because what he is doing is not working. Therefore, he thinks he is not working. On the other hand, he is at ease. He does this, that, this, that, and pop: he understands. Silence. And then he thinks something and does it as he thinks it. Everything will be a disaster if he is active in the wrong way. If he took this way, the way of saying, “How do I do it?” he is already in the world of gimmicks, not acting: illustrating, not doing. The other way, that moment of nothing, this is passive readiness. How did he get there? By refusing – yes, one must refuse – no, I renounce refusal; at this moment, he starts. He does it. That is all. It is simple, but it is most essential. This is what I mean.

Question: Why do you use the word ‘work’ so much? You never speak of joy or play.

GROTOWSKI: In my work – I hate this word. I hate this word worse than others. Among ourselves we use other words. There is a Polish word – to do – it does not exist in English or French. It is very different to understand the sense of “to do”, and to understand this word, but I will try.

If what we do does not bring more than joy . . . let me put it this way: joy is the minimum. Joy is the bare minimum.

There is something very sterile . . . it is what we call ‘sense of humor’: it is a social imitation of joy. Society says one must have sense of humor. This notion of humor is grotesque: jokes, for example, are the worst. I know a man who takes notes of jokes to tell others. This is proof of his sense of humor. So often in society, we laugh out of fear and terror. You may die of boredom, but we let this suffice. This man is an extreme case, but his story illustrates that social sense of humor of which I speak that is based on terror and can kill us all with boredom.

If you are in a group where everyone wants to prove his sense of humor, everyone says witty things about the situation; it is not just that they are repeating the words that bores you, or that you have heard the words before, but that they are repeating reality. They are trying to make life a record that can be played over and over and over again. There is nothing sincere in this. It is an ugly social game, nothing more.

Many actors learn tricks, like juggling. If they rely on these tricks, their moments become paradoxical because they benefits in two ways: 1. they know how to juggle, and 2. at the same time, they are funny. We applaud them for this as if it were a great accomplishment.

I know a man who imitates Huckleberry Hound. Imitators are very annoying and worst of all is they never know when to stop. Everywhere people are terrorized by the need for humor. I left humor behind for these reasons. This kind of humor is ugly; it’s grotesque, it does not produce joy, only boredom. True joy appears propitiously when it is needed, when it is essential. Often this happens after difficult effort or strenuous exertion, when one is, in a certain sense, less heavy – I mean “heavy” that way, also (American slang). One drops a weight. To carry the weight was physically, morally very tiresome. Joy is something one pays for – well, fortunately, not always.

There are moments when you don’t pay because you are in a state of grace. With this state, you are never heavy. But as I said, joy is not enough; it is only the minimum. I assumed you understood this. To do what doesn’t lead to joy is absurd. ‘Lead’ is a bad word there – it is wrong. The situation is not that there is something you must obtain. Really, it is something one must drop, eliminate, reduce. When you lose that kind of ‘heavy’, then the joy is there.